On Twitter, science and politics are topics best left to men. At least that’s the message TIME is sending with its list of “140 Best Twitter Feeds of 2013.” The annual roundup of top tweeters is overwhelmingly male, with women dominating just four of the 14 categories.

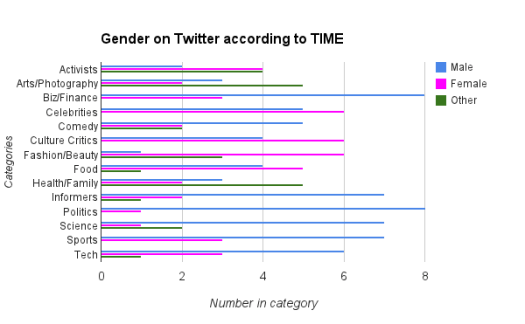

Female Twitter users are especially scarce in areas of the list devoted to science and politics, but they outnumber men when it comes to traditionally “pink” topics like fashion and food. The genders were evenly represented in a category devoted to activists. In all, the list included 71 men and 46 women, plus a couple dozen institutional accounts.* Here’s a full breakdown:

Does all this really matter? Probably not, but inclusion on a list like this creates buzz and a certain amount of pop-culture legitimacy. The fact that vast swaths of TIME’s selection are so male heavy is weird, especially when you consider that 60 percent of Twitter users are female.

TIME editors admit the list is “not comprehensive” and invite Twitter users to weigh in with their own favorites using the hashtag #Twitter140. But I can’t help wondering if they could have pushed a little harder to highlight women who meet the criteria of standing “out for their humor, knowledge and personality.”

There’s no dearth of smart women offering pithy political tweets. This crew, for instance, or any of the fine journalists suggested by Carrie Dann of NBC News:

As for science, I’ll bet this spunky social media user has some ideas.

(*A note on my methodology: I broke TIME’s list into three categories: male, female and other. The first two groups are self explanatory. I applied the “other” label to non-gendered accounts, most of which represented institutions. Careful readers will notice that 141 accounts appear on the graphs. That’s because one of TIME’s picks included two names, one male and one female.)