I spend a handful of nights each winter in the basement of a downtown church, pouring coffee and passing out dry socks to men and women with nowhere else to go. I’m among the hundreds of volunteers who, for the last decade, have helped operate a cold weather homeless shelter in Concord, NH.

The people we serve there have been the focus of a sweeping collection of stories, photos, graphics and videos published this week by the Concord Monitor*. The series, called Seeking Shelter, has given me a lot to think about both in terms of homelessness and the role of local newspapers.

I’ve learned a lot during my volunteer shifts at the shelter, but the Monitor’s series has taught me more. The city, write reporters Jeremy Blackman and Megan Doyle, is at an “unprecedented moment” in its history:

Concord’s homeless population has been growing for years, driven by a mix of economic instability, rising substance abuse and geography. State and local police have broken up many of the encampments in town, following a number of violent incidents and several deaths.

Community leaders have long discussed finding a more permanent solution, but they’ll need to act fast. Come spring, the shelter where I volunteer and a second one at a neighboring church will shut down for good.

The Monitor has addressed homelessness in the past through daily stories, photos and editorials. But this week’s series takes its coverage to a new level, one that bodes well for the practice of local journalism.

In his book The Wired City, Dan Kennedy** asks, “Can journalism have a theology?” He uses that question to explore the motivations and professional philosophy of Paul Bass, the founding editor of the nonprofit New Haven (CT) Independent. That publication’s journalism, Kennedy writes, is

based on a community-driven vision of conversation, cooperation and respect. It is a vision that sounds a lot like that of many religious communities, and it is the opposite of the top-down, we-report/you-read-watch-or-listen model of traditional news organizations.

I’ve been reminded of this passage as I’ve watched the Monitor’s series unfold this week. All of the players – social workers, policymakers, clergy members and the homeless people themselves – are portrayed as human beings facing complex challenges. Photographers Geoff Forester and Elizabeth Frantz earned the trust of the homeless community in a way that allowed them to document the lives of people who often prefer to remain unseen.

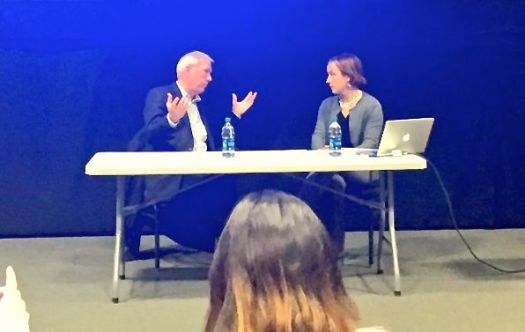

Perhaps most importantly, though, the Monitor has explored possible solutions and invited public conversation. Much has been written about the concept of solutions journalism, and the Monitor’s work this week is a good example of the genre. The newsroom also created the hashtag #homelessinconcord to organize online discussion. Tonight, the paper’s editors will host a community dialogue at one of the shelters about the issues raised by the series.

Not that long ago, traditional journalists may have labeled this as something too close to advocacy. It’s not.

Instead, it’s the kind of thing news organizations must do to remain crucial parts of the communities they cover. Kennedy makes this argument in The Wired City, exploring how local editors like Bass can foster as well as cover civic life.

The Monitor isn’t immune to the financial and existential challenges facing newspapers, but this series is an indication that, to the journalists in its newsroom, simple survival won’t be enough. Local news organizations should practice the kind of storytelling happening at the Monitor this week. It will be hard. It will consume scarce resources. And it must happen. No matter what.

Can journalism have a theology?

Yes.

And it’s embodied in the kind of collaborative, socially just and human storytelling displayed by the Monitor this week.

*I worked at the Monitor for many years, and was a consulting editor there this summer.

** Dan Kennedy was one of several fantastic faculty members who advised my graduate studies at Northeastern University last year.